What Remains Part 6: The Shape of the Living

-Written originally in June and posted on August 1st, this version features edits from September 2025, after life-events inspired revisions.

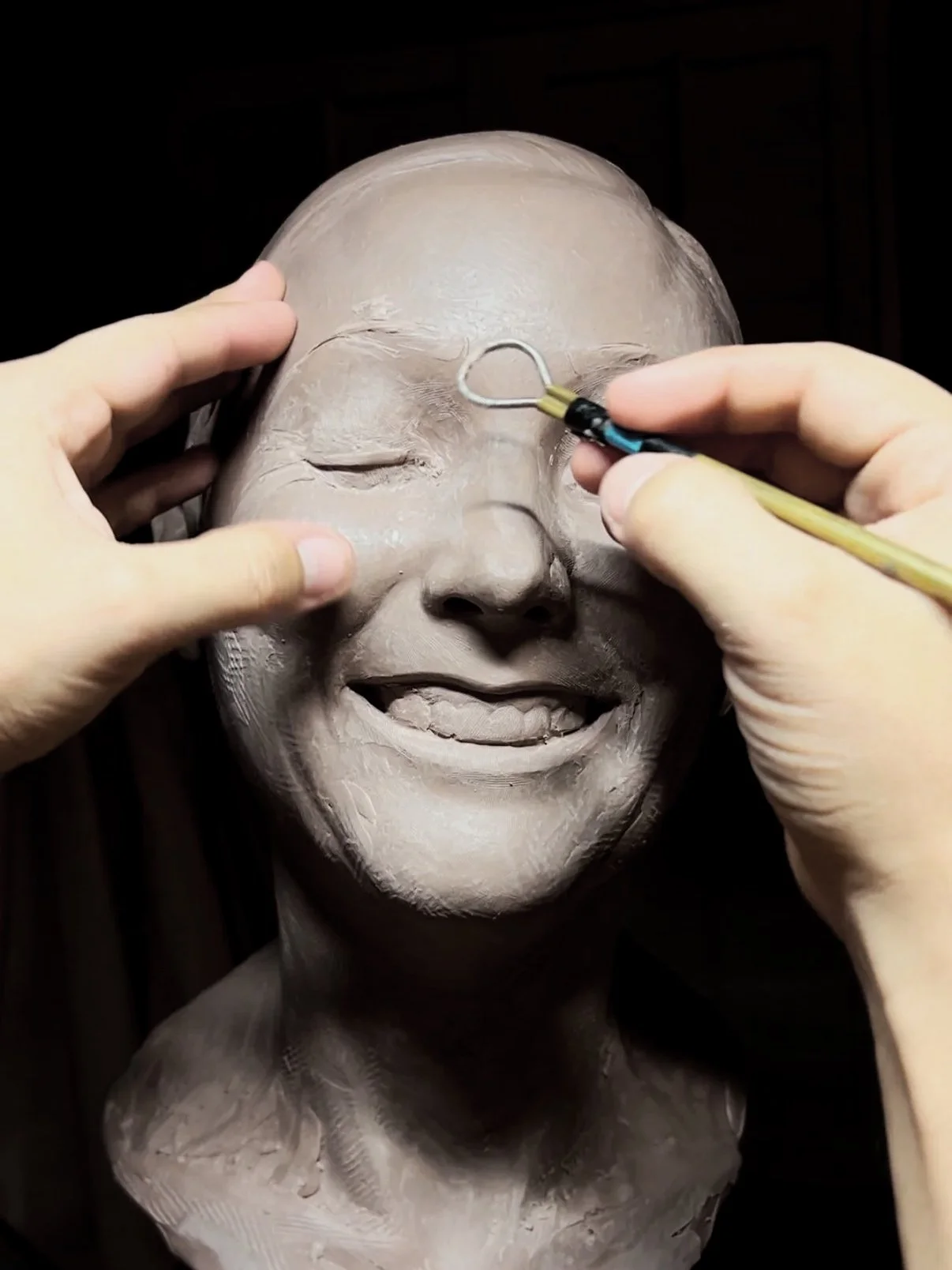

There is an apparent contradiction growing between my gradually strengthening posture to embrace impermanence with equanimity and my artistic labor – representational sculpture, which involves sculpting people realistically directly or through photographs. We, in the art community, often speak of "capturing" a moment, of preserving fleeting expressions in clay or stone, of making permanent what is inherently transient. Yet, with everything I have learned – and continue to learn – about the nature of consciousness, about impermanence, about the very essence of being alive, suggests that moments cannot be captured or recreated – that they arise and pass away like waves on water, leaving no trace, which is why the quality of attention we bring to bear while they swell becomes so crucial.

This paradox became acute as I returned to portraiture. Whether using clay or marble, if the moment I'm sculpting will never exist again—if Kelsey's expression as she reads, the particular quality of morning light across her features, the precise configuration of thought and feeling that animates her face—if all of this is already gone by the time I lift my tools, then what exactly am I doing with these months of careful carving? Why choose a medium that takes so long to reveal what was never there to begin with?

These questions loomed over me until I began to ponder if I was asking it backwards. I had been operating with the premise that sculpture was a technology for preservation or restoration: which is to say, that after all my education, both practical and theoretic, observational and representational painting, drawing, and sculpture was in some sense implied to be inextricably linked with attempting to describe and preserve the subject. I started to question this underlying assumption more critically and came to realize that I was holding onto this definition without ever examining if it was built on proper reason. Obviously, art can attempt to capture what is before the artist, but it doesn’t necessitate that it be the purpose of its practice. What I was actually discovering was sculpture operating for me as a technology for presence. The stone doesn't capture the moment—it creates the conditions for sustained attention to what is perpetually arising and passing away, not just the subject itself but the arising thoughts, feelings, and experience of them from my conscious perspective.

Consider the difference between a photograph and a sculptural portrait. The photograph does attempt to freeze time, to make a moment permanent. Click—and something that existed for 1/125th of a second is fixed forever. But the sculpture emerges through dozens to hundreds of hours of looking, contemplation, and action. It is the result of returning again and again to the subject physically and mentally. Each day I approach the sculpture, the person before me is subtly different. New lines around the eyes, a different quality of light, microscopic changes in the architecture of a face that is always becoming rather than simply being. The sculpture accumulates not a single moment but layers upon layers of attention—a record of devoted practice rather than documentation.

With this perspective in mind I return to the portrait of the person to whom I am the witness for. Today she is in her happy place, below the lemon tree, beside the grapefruit tree, being the sweetness between. she sips her coffee as she reads a few pages of her book on microorganisms. Meanwhile I scrape the edge of her marble cheek as I catch her fleshy one in my sights. She takes a break, a new accessory for her studio-wear has arrived in the mail. She insists that I opine on the aesthetics of such a working-lady’s headdress. I attend, I witness, and approve. I return to continue to shape the cheek on the sculpture but this time settling into the sensation of how at peace and contented she is with the acquisition of such a simple garment. It’s clear seeing of this kind – the kind where gratitude comes flowing generously – that has filled my practice. It is a way of making contact with the life I have, as the wave of tranquility swells until it dissipates back into the sea of our lives. I know this moment won’t last; neither will this sculpture; it too will erode with the winds of time long after she and I are both gone, but until then it will hold evidence of my witnessing the impermanent life we have lived, are living, and our life yet to come.

As I work on this small object of my attention, I am more acquainted with my mind, its character, and the patterns of its storms. In my sessions, thoughts and ideas percolate in consciousness; I let them arise, observe them, and allow them to pass. Few linger. They color the moment, and I try to sit in them as they inform my tool marks, the pressures of my sanding instruments, and the focus of my sight. The more I practice this way the more moments like this infuse even the most mundane activities throughout the day. The act of looking, attending, and witnessing can be settled into even without the sculpture tools in hand. At times I am inspired to use other tools to create with gratitude, often taking the form of letters to the subject of the artwork. As the sun lowered, the time for carving came to a close. As the time for creation swelled then dissipated, so came the time for the maintenance of our lives. Domestic duties can just as easily give rise to gratitude; I wrote to her:

Threads

I folded your clothes, still warm from the wash, how empty they seemed without the structure of you propping them up. Warm only for a few more moments, until the chill of the empty room regulates them back to "room" temperature. With bends and flicks they collapse into a pile of threads. Without you, all your outfits, your dresses and socks, they sit in wait to be chosen, unfolded, and supported by your radiant structure.

As I look up after placing the last of your garments to see a collection of our wedding photos I, to my shame, rarely look at for any extended period of time. I smile. There you are in photographic stills, bringing structure to your white wedding gown and bringing structure to me. You chose me, even if without you at times I feel I could collapse as easily as an unworn garment. You are in these pictures enamored by the man I was, seemed to be, and may yet be. It brings me immense joy that while this room, like the clothing, is empty of your presence, you are but a few steps away busy in our kitchen. Bringing more structure to our world, cooking us nourishing meals so that we may fill the coming days with effort towards our mutual goals.

Your structure makes a man of the threads of which I am woven. With you I stand more upright. Thank you for existing.

I can hear the skeptical reader whisper to me that this is all well and good, and easy, while life is positive, going well, and full of promise. Perhaps, And then again, perhaps not. I did say at the outset that this posture of enjoying what we have because it won’t last cuts the other way. I keep my eyes and focus on her because I will lose her. She will fall ill. She will die. She is finite. It makes this moment, this pocket of foam over the crest of this momentary wave feel all the more wonderful even if it is destined to crash below. The phone call came, I wrote again:

Flight Through the Grey

The Arizona sky was grey.

I woke to a shriek. A yell. A cry. As I flung the sheets from the bed and grabbed my glasses to get to the door and run toward you, I knew. I was too late. Running to the room where you were, I knew, I was too late. I opened the door and—your voice shaking, eyes red, a phone to your ear—you yelled: "My mother's dead!"

I held you, your body trembling, my arms attempting to contain the agony threatening to tear you asunder. I could feel the sadness, anger, and regret emanating from you as vividly as the moisture of your tears on my shoulder. There was no consolation to give; no appeal to any idea or story that could remedy or blunt the sting of your present circumstance.

Over the next few days you will likely hear it all: "She's in a better place." "You'll be reunited someday." "It was her time, God has a plan." Greatest hits and their remixes. They are nothing but the potato chips and ice cream of philosophy—junk food to appease a mind struck head-on by the absurdity of our existence. Easy to consume today, but in excess, crippling. Soothing words that may make the pain feel more manageable for a moment, yet slowly dull the truth of what has happened.

Now there remains a body where your mother once was, and I have a deficit of words for you. The emptiness of my worldview will seem heartless to most, but it is not made of the ready-made opiates of the mind. I will not tell you there is some greater plan. I will not tell you this is for the best.

All we can be certain of is that you are struggling for a logic to the absurdity of this event, and I am struggling with the impotence to solve it for you. That struggle is all we have, the mere fact that we have these drives is enough.

As we sit here in this tin can flying across the grey sky toward your childhood home, I'm holding your hand, still searching for the "right" words. I lose myself to the fantasy of making you whole again, as if there were magical syllables I could utter to bring you instant joy. But that fantasy would only separate me from just being here—to focus on the way you blink, how your hand moves ever so slightly in mine, how it squeezes from time to time, how a small tear catches a highlight from the window as you stare at me.

I'm here to witness the unfolding of your life for as long as we have it. I'm here not to dull your pain, but to help you navigate it, for as long as it lasts—which will be for as long as you live. To tell you that it gets better, or that it goes away, would be tantamount to saying you'll forget her. And forgetting her would be losing your love for her to the opiates of feel-goodery.

It's heavy. Only you know how much it weighs. This will not be easy. But when you tire, I will be here to carry it with you, for as long as we must. It will make us stronger—strong enough to be open to the suffering of not just each other, but all the helpless sentient beings we will meet in our absurd time in this terribly beautiful universe.

We hurt. We remain. Together.

I could not take her pain away. I could not preserve what was lost. But I could practice presence. The same patience required to reveal a form in stone was required of me here—to stay, to witness, to not reach for easy consolations. It became my turn to be the stone. Patient and steady, enduring not by resisting grief but by absorbing its weight without splintering. As she grieved with her family, I was there. As they argued in futile attempts to rationalize the unfathomable, I was there. As she cried herself to sleep, I was there. What I had learned through marble—endurance, attention, a willingness to return again and again—was now lived in the silence beside her.

In the days that followed I watched her scour and collect every visual remnant of her mother. She became an archeologist of memory, piecing together what remained in photographs: still frames, a frozen smile, a hand mid-gesture. These images were precious, and I would never deny their worth. Yet watching her hold them also clarified what my own practice was becoming. A photograph embalms an instant. A sculpture—or a letter—embodies the hours of presence it required. They do not preserve her, or me, so much as they testify: I was here, attending.

Photographs of Kelsey will be precious if I outlive her. But even more precious to me are the intangible, mindful, and attentive moments I have recorded in carving and in words. Not attempts to rescue her from time, but evidence of the life we shared while we had it. Folding her clothes, tracking the contour of her marble cheek, holding her trembling hand on a flight through the grey—these are not acts of preservation but of witness.

I think again of Andrés on El Malecón, teaching me to name the colors of passing cars. He wasn’t trying to capture them or make them permanent. He was showing me how to look with intention, how to return again and again to what is before it vanishes from view. Not preservation, but practice. Not capture, but cultivation of the capacity to be present with whatever comes, until it is gone. The sculpture, then, becomes evidence—the physical record of attention rather than its primary purpose. The same is true of these letters. They are the residue of presence, not attempts at immortality.

When I sculpt Kelsey now, I am not trying to make her permanent—I am practicing impermanence. Each day she is slightly different, and each day I must meet her freshly. The stone changes too, yielding new possibilities as old ones are carved away. Nothing is fixed. Everything is becoming. The sculpture emerges as a collaboration between my attention and the ceaseless flow of time during its radiant springs and cold winters alike.

This is the shape of the living: not static form but dynamic process, not captured moment but cultivated presence, not preservation but perpetual practice of seeing what is here as it swells, until it dissipates again.