What Remains Part 7: Make Thee A CAto

The Roman bust: an iconic sculptural genre that predates the Italian Renaissance and descends from the Greek tradition, was reserved for ranking politicians, statesmen, generals, and, of course, emperors. Sometimes just the head, but very often featuring a cuirassed torso—chest armor—ornamented by a draped military cloak known as the paludamentum. This combination of martial garb and carefully rendered visage signaled both strength and status.

To have one’s likeness rendered in marble and made public was a communal display of reverence, respect, and sometimes love. The act of immortalizing a person in this way often followed a great achievement—years of service, intellectual contributions, hard-fought elections, or the conquering of peoples scarcely different from one’s own. One could say the practice was reserved solely for those in positions of power, earned and unearned alike. You would be right to think this. Not to mention that nearly all busts of this genre were made of men—men who more than likely had stained pasts or blood on their hands to earn the honor.

While I acknowledge this troubling truth, it is the act itself—the making and placing of the sculpture—that fascinates me, not the potentially compromised man depicted in cold stone. Rather, it is the act of contending with a piece of stone and shaping it into what it is not, and of having the likeness of a chosen person made public in a seemingly futile effort to have their face remembered. And then it falls on the community to want to remember. The presence of a bust in the town square is, in a sense, a collaborative effort. The people who inhabit a place ultimately have a say. There are countless acts of vandalism, violent toppling, and gentle replacement of public sculptures where the people have declared they’d had enough remembrance. Memory is a strange thing that way—it can bring joy or pain.

Shown here is a young Marcus Aurelius, on display at the Uffizi Galleries, Italy.

Growing up in Cuba, I was surrounded by busts of José Martí. They were everywhere—schoolyards, clinics, traffic circles, apartment courtyards—so many that they faded into the landscape the way lampposts do. Martí’s face became part of the island’s architecture: the pointed mustache, the severe brow, the watchful tenderness. No one needed to defend these busts. No police guarded them. No one whispered about them. They stood because the people wanted them to stand. Even when a bust was chipped or sun-bleached or leaning slightly from decades of rain, someone would eventually repaint the pedestal or place a small bouquet at its base. Martí did not endure because the government demanded it; he endured because ordinary Cubans still chose him as a model for living and striving under uncertain circumstances.

Fidel Castro, by contrast, appeared almost nowhere in three dimensions. Not a single official bust. No statues in town squares. No heroic marble likenesses for future generations to pass by on their way to school. For a man who governed for nearly half a century, the spatial absence was startling. There are reports that he forbade sculptures in his image; however, I suspect this is so that no video was ever captured of him being toppled in three dimensions to rival Saddam Hussein’s iconic tumble.

His presence lived instead on murals and billboards—ephemeral surfaces, easily repainted, quietly defaced, torn down, or allowed to decay. The state erected them; the people tolerated them; but no one treated them as sacred. A mural could disappear overnight and return the next week under a fresh coat of paint, its authority as thin as the layer of pigment that formed his face.

Even as a child I sensed the difference. Martí is remembered. Fidel was tolerated, and sometimes not. Martí’s likeness belonged to the people. Fidel’s likeness belonged to the state’s political machinery. And that taught me something long before I had the words for it: A likeness only survives if others grant it legitimacy. Marble is strong, but the consent to exist by those who do the memorial maintenance is stronger.

The endurance of Martí and the absence of Fidel revealed that public remembrance is never truly mandated from above. A figure may dominate a nation’s politics, but that does not guarantee a place in its plazas. Memory must be earned, and it must be renewed continually by the people who walk past the monument each morning, care for its plinth, and trim the surrounding greenery.

This is what fascinates me about making a bust. The stone itself means next to nothing. What matters is whether a life deserves to be held in the open, offered to the gaze of others, entrusted to the public to remember or refuse. Even portraits that remain within families raise the question: if yours were to be made, would your great-grandchildren go through the trouble of preserving, moving, and showcasing it? Or would yours be the likeness that fades?

This tradition—if it needs reminding—comes from an era before the photograph, before your iPhone. There are countless faces, belonging to fundamentally good and unforgivably vile people alike, that are lost forever in the fog of time. We have a strange relationship to images in the modern era. Images are ubiquitous to us. Many people born in the late 20th century, as I was, have photos of loved ones who no longer look like their former selves. And more interestingly, those born in the early 21st century will have detailed, high-resolution images of themselves and their families readily available in their pockets for the rest of their lives. Our phones even generate videos of these photos in a curated stream meant to remind us of past trips, life events, and the shape the world once took. In Ancient Rome, there was no such luxury. Art was the way of imperfectly recording the world—through painting and sculpture.

And so the question then follows: who is worth remembering? It’s a hard question. And yet, we make it daily—when we choose, or choose not, to spend time with those we care about.

I don’t call my mother nearly as much as I once did. That hurts to write. Though I know I am making efforts to correct this habit, there are parts of her life I neglected to attend to in the name of unrelenting “busy-ness.” I am, in effect, indirectly choosing not to check in with her—to hear her voice, how it changes, how it remains familiar. To check in with the quality of her life so that I may chisel a sculpture of her in my memory.

Seneca reflects on the shortness of life: it is not that we have little time, but that we waste so much of it. I am embarrassed to say that in my career path I have strayed very far from home—not just physically, but even down to keeping communication lines open and frequent. It is a shame that I only know how to process this now with a renewed drive to make, create, and attend to the faces in my life while they’re still here. It is the reason I’ve been writing this whole time. I want them to know how much I think of them—how much I preemptively taste their eventual absence.

It doesn’t have to be philosophical or sculptural theses that bring you closer to those you fear losing, dear reader. It can simply be the conscious choice of attention, in whatever form you are able to offer. This is enough.

At the time of writing, I am exploring a sculptural experiment—a different kind of reconstruction. This time it doesn’t entail laying down anatomical landmarks on a fossil and pulling a likeness from the fog of time using mathematics and statistics. Rather, I aim to restore the likeness of a person from old photographs—to bring them honor in the present for a deed they performed that shaped the life of a small creature born in an unimportant town, on an unimportant island, on an unimportant rock hurling through space.

Dear reader, if by now you’ve guessed the subject—perhaps recalling the image I painted earlier of him carrying me out of my crib from On He Who Attends—please know that my eyes water as these words emerge on the screen. Perhaps without knowing, with a simple gesture, Andrés gave me not just a chance at a good life, but also instilled in me a hunger for meaning, purpose, and a yearning to attend to the shape of the living. This reflection comes at a time when Kelsey and I are discussing having a family of our own, and I am feeling the weight of that forthcoming responsibility. With this orientation toward honoring and attending the present, I felt it fitting to begin with the one who taught me decisiveness and attentiveness—traits I will need to embody more and more in the coming years.

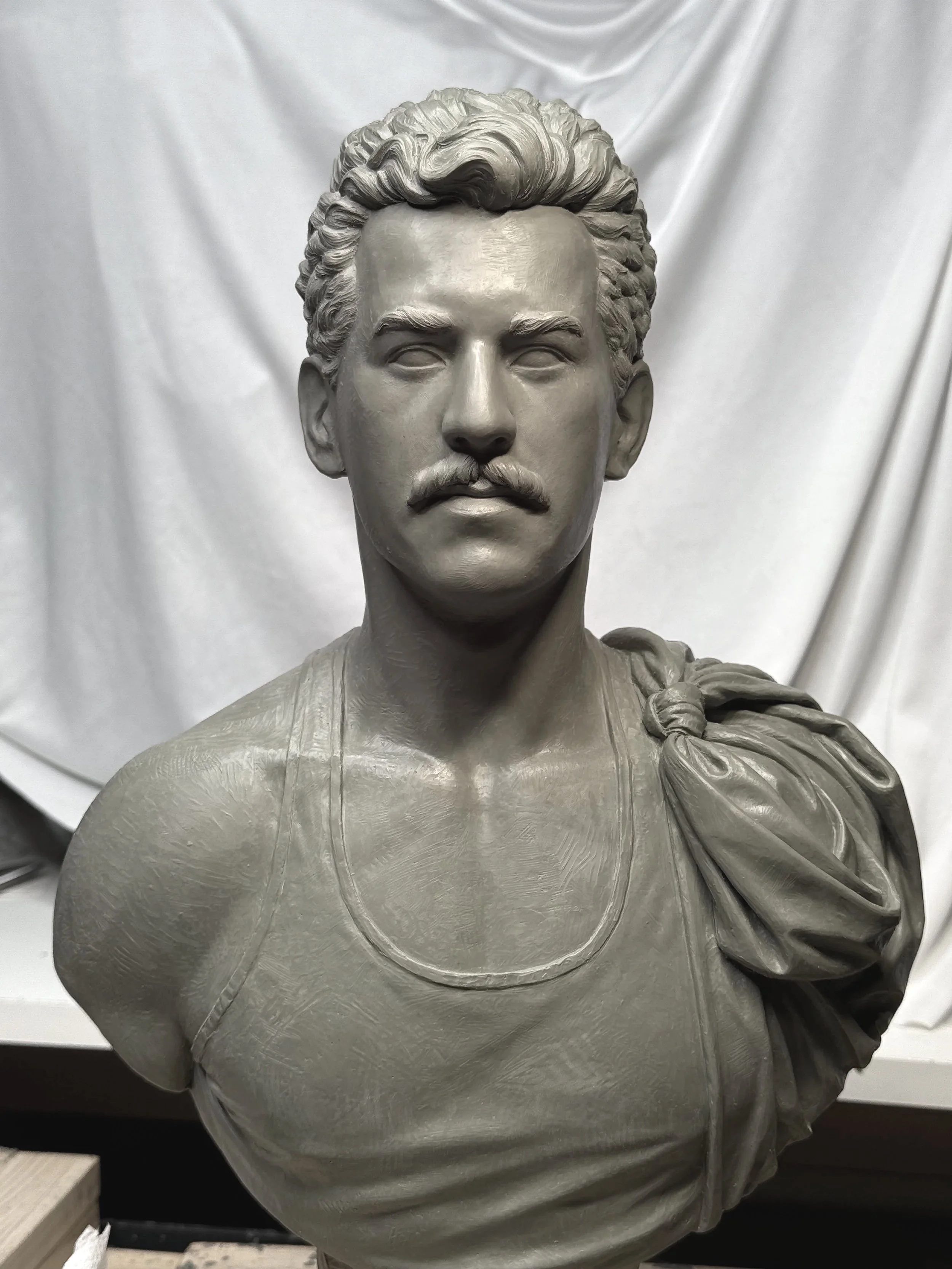

The sculpture is of Andrés, wearing the simple garment I described before—a tank-top-like shirt seen in a few photos from 1992. A cuirass fitting for any war of purpose. On his shoulder, in keeping with tradition, his paludamentum is a knotted bedsheet he once used to swaddle me—a symbol of the warmth and security he draped me with when he made his decision. An emperor’s treatment for a gesture that rippled through and changed the course of my life.

But the other shoulder is left bare.

I wanted to show that this wasn’t a man destined for depiction in marble from the start, but someone who stepped forward in a moment—vulnerable, undecorated—and still chose to carry the weight. Like Marcus’s ivory shoulders, the strength was not inherent; it was revealed in the moment of coming to terms with what lay ahead and pressing on despite a sea of eventual and inevitable troubles. “The obstacle is the way,” as an old emperor once said.

Epictetus, the slave turned Stoic lecturer, advised his students to choose a sage or model—“Set before yourself a Cato or a Socrates,” he said—and imagine how they would act in moments of difficulty. Not because perfection was possible, but because having a standard sharpens one’s moral compass. Perhaps this is an appeal to meaning outside of what is on offer from this cold, seemingly meaningless universe. Perhaps. But the boulder calls me to keep pushing.

Make thee a Cato, I tell myself.

I suppose that on the eve of my possible fatherhood, with its certain trials and obstacles, this sculpture is my own quiet variation of that mantra.

And so, I have set before myself a Cato.

A father, not a conqueror.

A tank top, not ornamental armor.

A piercing gaze, not a sharpened sword.

Not an appeal to meaning, but a meditation on moving one’s life forward despite not knowing.

But still—a gesture rendered in stone to remind me:

how to stand: upright.

what to carry: the vulnerable.

and when to act: now.