What Remains Part 4: The Return to Attention

The weeks following my return from Italy unfolded in a curious rhythm—a tempo neither fully oriented to the past nor completely aligned with whatever future awaited. The marble dust still settled into the crevices of my fingernails, a tactile reminder of what remains of my massive undertaking an ocean away that contrasted with the emptiness of my studio calendar. The experience of achieving a large-scale marble piece had come and gone. For nearly a decade, I had known exactly what my hands would be doing tomorrow, next week, next month. Now, that certainty had evaporated, leaving behind not anxiety but something more subtle—a spaciousness I hadn't felt since childhood.

I found myself tracing old paths without purpose. My body would instinctively move toward the shelves of calipers and measuring tools, my hands reaching for objects no task required. My studio remained as it had been—specimen skulls and in-progress heads lined my shelves, modeling tools arranged by size, reference books stacked by frequency of use—but the central workbench where reconstructions took shape stood empty, like a stage between performances. There was nothing to solve.

It would be easy to romanticize this period as one of profound quietude or immediate clarity, but honesty demands I acknowledge its messiness. Some mornings I woke with a lingering urgency, I found myself automatically pulled to improve or come up with a new aspect of my specimens to focus on, as if my hands hadn't yet received the message my mind was processing. I would catch myself drafting emails to my scientific colleague about new ideas or approaches to facial reconstruction, only to abandon them half-written. The scientific language that had once been my fluent tongue now felt both familiar and foreign—like returning to a childhood home, unchanged yet unrecognizable. Other days, I'd sit for hours in silent contemplation of the empty workbench, not in meditation but in a kind of arrested momentum—a boulder paused mid-roll, neither at summit nor valley floor.

What emerged from this suspended state wasn't revelation but questions—questions that circled back to where this journey began. Having eulogized the past through La Piedad, I found myself confronting again that fundamental question: what does one do with a life that ends? The absurd hadn't disappeared; like the surface on a sculpture, it had simply shifted form subtly. The boulder remained at the foot of the hill. After years of sculpting faces that no longer existed, after holding the skull of a child who died millions of years ago, after attempting to resurrect what was lost through clay and mathematics—I now found myself meditating on the impermanence of all things, including my own body that would one day be as inaccessible as the Taung Child's.

The questions transformed: No longer "How did our ancestors look?" but "How do I look at the world knowing everything in it—including myself—is temporary?" Not "How can we accurately reconstruct the past?" but "How might I authentically inhabit the present while accepting its impermanence?" My gaze began to shift from fossilized remains to the living faces around me—my wife, my colleagues, my students, my friends. I realized with a sudden clarity that if I'm fortunate enough to live a long enough life, my prize will be to watch everyone I love die. They too will join the vast sea of the unknown, their inner lives becoming as inaccessible to me as those of our ancient ancestors. The parallel struck me with unexpected force: I had spent a decade trying to uncover what was already lost, while potentially missing the joys of the mystery that breathed right before me. If I continued excavating only the past, I would miss the fleeting, irretrievable present—the only moment in which connection is actually possible.

It was around this time that I was rereading the works of the Stoics, namely Seneca and Epictetus. Seneca's "On the Shortness of Life" no longer struck me as merely interesting philosophy but as urgent counsel: "It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it... Life is long enough, and a sufficiently generous amount has been given to us for the highest achievements if it were all well invested." In college, I had approached such texts academically, mining them for insights to incorporate into papers or discussions. Now, I read them as practical guidance for navigating this unfamiliar terrain. The Stoics' preoccupation with mortality no longer seemed morbid but clarifying—an invitation to recalibrate attention in light of finitude.

Within Stoic writings and reflections I encountered regularly a tacit implication that when we mourn the dead, it is often the sting of regret, the cost of inattention, that deepens the hurt. This confrontation with all the decisions not to call that person, not to spend time with them, and the failure to tell them you love them when you had ample chances to, is what causes our grief and loss to deepen. This insight was powerfully echoed in a speech by neuroscientist and philosopher Sam Harris, reflecting on awareness of our deaths: "You've had a thousand chances to tell the people closest to you that you love them. In a way that they feel it. And in a way that you feel it. And you've missed most of them." For anyone being honest with themselves, this observation is arresting. No matter how much I pay lip-service to my love for my grandmother, I don't call her enough, even if just to engage in the inevitable mundane, unimportant small talk about her pets and her medical woes, for it to end with blessings from a god I don't believe in. One day, there will be no option to call this person that carried me, fed me, and sang me to sleep when I was uselessly a year old and unemployed.

Having recognized this blind spot in my mindfulness for the living, I found myself recommitting to my deep interest in contemporary mindfulness practices—not as spiritual bypassing or escape from the discomfort of existential dread, but as concrete methods for developing what the Stoics had prescribed: present attention. The meditation cushion became as much a workbench as my sculpting table had been, though the materials were subtler, the results less tangible.

What surprised me most was how these seemingly disparate traditions—Stoicism with its Roman origins, mindfulness with its Buddhist roots—converged on remarkably similar insights about attention and impermanence. Both recognized that suffering arises largely from our relationship to reality rather than reality itself. Both offered practices for cultivating clear seeing. As mindfulness teacher Joseph Goldstein describes, suffering is often fueled by "unskillful" patterns of mind—those shaped by greed, hatred, and delusion—and by "wrong view," the fundamental misperceptions we carry or cling to regarding permanence, self, and the sources of happiness. This perspective offers a new lens on the Sisyphus myth: his suffering, from a Buddhist perspective, lies not in the futility of his task, but in his wrong view—his attachment to the stone's permanence atop the hill. Both Stoicism and mindfulness suggest that peace comes not from controlling circumstances but from attending fully to what is: to clearly see, without appeal to distraction, and bear witness to the unfolding present experience before us.

As such, my practice of mindfulness deepened, and I regularly found myself waking up and finding stillness on the cushion. Not with the goal of perfection or achieving some heightened state, but with a deepening appreciation for the simple act of noticing—the slight coolness at the nostrils on inhale, the warmth on exhale, the rise and fall of the abdomen. When my mind wandered to unfinished reconstructions or uncertain futures, I would simply note the wandering and return to breath, finding that the space between thoughts gradually expanded.

What changed wasn't the practice itself but my relationship to it. During eyes-open meditation sessions, due to my usual position in my backyard, I would face my home—this modest desert paradise my wife Kelsey and I were slowly developing. In moments where I would be confronted by inevitably unskilful and trifling thoughts like: "you're in your 30's, you should be a famous and wealthy artist by now, instead all you have is this." In moments like this, as those thoughts wormed their way into my mind, they were met by the clear seeing I was developing. This was enough, there is nothing to solve. I, to whom nothing was ever guaranteed, had a free early morning, a home, trees growing nearby, my cat Lucy on my lap, and my wife sleeping inside the house. I had this moment. There was nothing to solve.

Where once I had approached meditation as another skill to master or tool to employ, I now recognized it as something more fundamental—a way of being rather than a technique to perfect. The questions that had previously haunted my practice—What was I accomplishing? How was this advancing my work?—began to lose their grip as I recognized them as expressions of the same achievement-oriented mindset that had driven my scientific pursuits. As my practice deepened over months, subtle shifts emerged in my everyday awareness. Details in my immediate surroundings that had long receded into the background now came into sharper focus—the precise quality of morning light on my kitchen counter, the intricate patterns of bark on the tree outside my window, the complex soundscape of my neighborhood. This wasn't merely aesthetic appreciation but something more fundamental—a return to direct perception before conceptual overlay, without liking and disliking—a way of seeing that preceded and now transcended my scientific training.

One morning, again during an open-eyes practice I found myself making mental notes of colors without paying close attention to what the objects were. It brought forward a memory my parents would often share with me. I was likely 1-2 years old, so the memory is not exactly mine alone—it's more of a vicarious memory since my parents made regular reference to it as I grew up. In a flash I was back there—sitting with Andrés on El Malecón, the sea wall that faces the United States, in Havana, Cuba, learning to name the colors of the passing cars. "Azul," would say the man who would ensure I never felt the sting of fatherlessness, as a blue Chevrolet rolled by. "Rojo," as a red Ford followed. My parents would often reference this as a tongue-in-cheek way of taking credit for my painting abilities, in a way saying "see, we taught you the colors." I always knew it was them feeling proud that I was starting to make something of my obsession with recording the world through my art, but it wasn't until now that I fully recognized what he had actually been teaching me—not merely colors or makes or models, but how to direct attention itself. Not analysis, not categorization, but simple, direct seeing.

This event was countless times recalled by my parents in a fond light at any age, something they regularly referenced to me as a very peaceful and tranquil time in their lives. In the midst of hardship in Cuba, there were still moments of clear and focused attention on the task at hand. My adoptive dad focused on giving me a peaceful day with his attention, and me focused on one simple directive: What color were the cars?

This realization brought with it a wave of emotion I hadn't anticipated. I had traveled thousands of miles, earned degrees, published papers, created works that stood in galleries—yet I was circling back to wisdom a young man had shared with a child on a seawall in Cuba. The simplicity of it was both humbling and strangely liberating. This echoed to me a familiar concept discussed by not just the Stoics, but Ancient Greek thinkers alike: Eudaimonia—a state of well-being, tranquility, or human flourishing. Philosophers agreed on its value but disagreed on how it might be attained.

As I shifted my attention from the past to the present, from reconstruction to witnessing, I began to glimpse what felt like my own version of this state. Not in grand achievements or scientific breakthroughs, but in small moments of deliberate attention: noticing the changing expressions on my wife's face as she spoke, registering the subtle shift in a student's confidence after mastering a technique, observing the interplay of light and shadow across familiar objects. In these moments of attending fully to what was before me, I found a quality of stillness and presence that had eluded me during years of scientific pursuit.

These insights reminded me, too, of what Arthur Schopenhauer once observed: that much of our suffering stems not from life's cruelty, but from our endless striving to make it something other than what it is. In moments of full attention, when striving fell away, I could glimpse a different relationship to the world—not one of conquest, but of quiet accompaniment.

The image of Sisyphus returns to me. As tired as he is as a metaphor, I found myself tired by the striving. So I was back to where I started, where once I rolled the boulder to ensure it stayed atop the mountain, this time I would roll it to enjoy its movement. To smell the crushing grass beneath its weight, to enjoy the fact that I still could push at all, and push I must; "to take arms against a sea of troubles, and by opposing end them." Thus "We must imagine Sisyphus Happy," Camus echoed; I returned to portraiture—this time, not as a problem solver always dissatisfied with coming up short, but as an act of witness.

Witness. This word found me again and again as if to call me back to a piece I had started and abandoned a few years prior. I had sculpted a portrait of my then fiancé, Kelsey. I never directly told her what the piece was about. This was while I was working on the initial clay work for the Pieta. For me it would turn into a physical embodiment of witnessing her life and would tie into the vows I would deliver on the day of the wedding. At the time I was playing with drapery in my work without fully forming the conceptual framework I have today. For aesthetic cohesion and with some understanding that it was related, I chose to partially veil her smiling face, revealing only part of her face to explore the unknown aspects of her that I might eventually uncover as our marriage unfolded. This piece was shown at my wedding, still in clay. As malleable as the clay is, so was my relationship to this piece. It now called for my newly refined sense of attention and witness. I would explore this foundational work in a new way.

This piece began sculpted in clay from life as she read a book as she does on many of our quiet reflective mornings. At the time, the portrait was capturing the person with whom I intended to spend my life and subsequently focus on how much about that person I still did not know, and how I would commit nevertheless. Interestingly, the piece had a scientific undertone as if the enigmatic uncertainties of this beautiful creature were puzzles to solve.

There was nothing to solve.

This time, however, I would perform the portrait in an enduring, slow-paced, and methodical material: Marble. As a smaller, more meditative version of the original, this one would do away with any problem solving. Rather, this portrait was to be a meditation on being fully present with the life I have as it is. I, born in Cuba, during the fall of the Soviet Union during a period of economic and social hardship, now found myself with a home in the relative safety of the Arizona desert, an American wife, and the privilege of having been a university professor. Reflecting on Seneca yet again: "It is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor." From my vantage point, a free Saturday ahead of me, the sun warming the humble plants behind Kelsey, there was nothing to solve. There was only this moment to witness before it became a fossil in my memory. I looked at her, and with my hands, attempted to shape the clay so as to make physical the vow that I would be here to witness her life in the present regardless of how it unfolds. There was nothing to solve. Like cars passing by, I noted her particularities, the small mole over her right brow, the shape of her smile, the contour of her very being. There was nothing to solve.

Like La Piedad, this sculpture also incorporated the use of drapery, a gentle veiling—but this time, the covering reflected a different purpose entirely. Where the drapery in La Piedad acknowledged the limitations of science to reconstruct the past, here it celebrated the mystery of the living present. The veil was no longer a concession to epistemological humility but an embrace of ontological wonder. It was not covering what cannot be known, but partially revealing what is constantly unfolding.

In La Piedad, the veil represented a kind of mourning for knowledge forever beyond our reach. In The Veiled Muse, it became an invitation to patient witnessing. The fabric partially obscuring Kelsey's features wasn't concealing a fixed reality I failed to capture, but acknowledging the fluid, dynamic nature of a living being who would never be fully knowable—not because of scientific limitation, but because of life's inherent becoming. This shift in the meaning of the veil mirrored my shift in orientation—from trying to resurrect and fix in place what was long gone to attending to what continually emerges. Just as I had once used drapery to mark the boundary between the knowable and unknowable in our evolutionary past, I now used it to honor the ever-changing present. Her face, half-revealed through the gentle folds, carried not answers but mysteries yet to unfold: joys, sufferings, transformations I could not predict but could commit to witnessing.

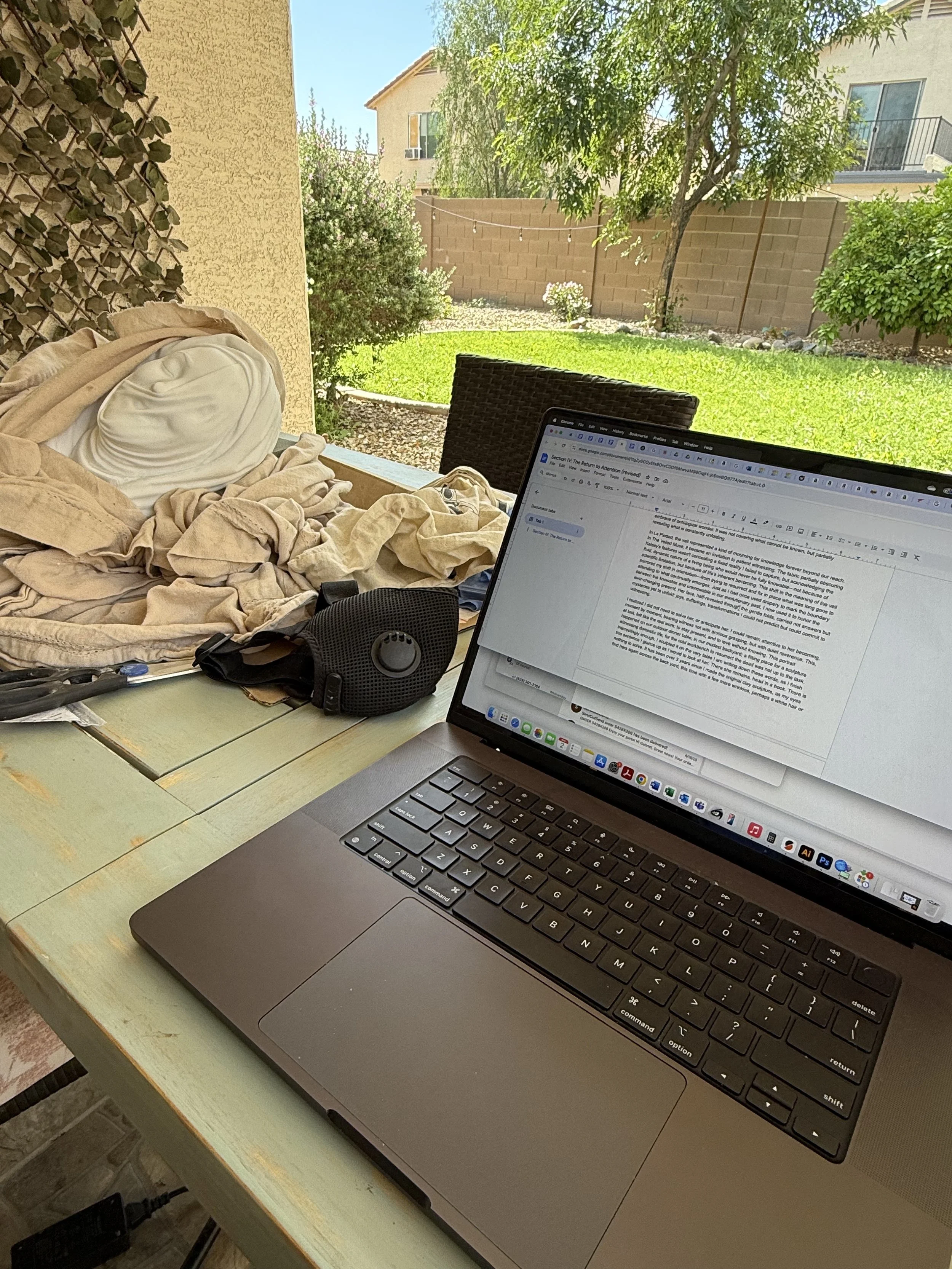

I realized I did not need to solve her, or anticipate her. I could remain attentive to her becoming, moment by moment, bearing witness not with anxious grasping, but with quiet reverence. This, at last, felt like the real work: to stay present, and to love without knowing. The initial clay portrait happened on our outdoor dinner table, in our modest backyard—a fitting place for a sculpture witnessing domestic life, for the cold workbench to resurrect the dead was not up to the task. It was at this table that I returned to carve the stone in her likeness, to not just look at her and record what I was seeing, but to sit mindfully with the stone, to perform an act of witnessing. To be here with her, as someone in her world chooses to spend their time glancing at her, wishing to remind her that she is enough, more than enough.

My mother once told me a story of how she was made to feel under the gaze of an unkind man, how her postpartum and aging appearance seemingly disqualified her from the love and attention of someone who was greatly responsible for those changes she underwent. This work, my attention, and gaze would attempt to repair some of the damage my antecedent caused. It may not balance the scales of justice, but my mother can rest assured knowing her son will not repeat the "unskillful wrong-view" she was wounded by.

I now find myself on that very same table with my tools beside me ready to engage in loving skillful attention—to practice right-view. The stone lays there as I am writing down these words. As I finish this sentence I glance up as I would to look at her. There she remains, head in a book. I then glance at the unfinished boulder-like portrait, I smile, like the free Sisyphus might have at seeing the boulder at the base of the hill as he readies himself for the coming push. He might tell himself, "There is nothing to solve." I stretch my hands, as the stone calls me to return to attention. It has been over 3 years since I made the original clay sculpture, as my eyes find hers again across the back yard, this time with a few more wrinkles, perhaps a white hair or six more, but her radiant smile remains. No equation or statistical model will reassemble this moment. It's here, until it's not.

There is nothing to solve.