What Remains Part 3: The Veiled Eulogy

There it was, the half-finished reconstruction of the Taung Child lay before me—the 5th time I had attempted a new methodology on this specimen—a testament to years of scientific pursuit. I gazed at my skeletal Sisyphean boulder, rolled to the base of the hill yet again. This ancient child, whose fossilized remains had been hidden from us for 2.8 million years, represented both the progress of my scientific work and its inevitable incompleteness. The more precisely I measured, the more meticulously I sculpted, the more aware I became of what would forever remain unknown. The child's life, brief as it was, contained a multitude of experiences I could never reconstruct.

It forced me to confront my fundamental questions more seriously: What constitutes a human? Is it the tapestry of muscles beneath their skin? Their vault of memories? Or perhaps their inherent vulnerabilities? These questions had driven me to employ mathematical equations and predictive models in attempts to anatomically resurrect beings from the distant past. While revealing statistically significant and scientifically relevant facts about their physical forms, the endeavor of employing statistical models in the act of sculpting their portraits also highlighted the limitations of scientific methods in capturing exactitude and accurate representations of their faces.

More sharply, it made clear that the enigmatic facets of human existence—the emotions, thoughts, and unique individual experiences of these beings—are unlikely to be known or calculated using equations and statistical analysis. This thought, that the object of my artistic and academic search was likely unattainable, felt like a profound loss. I moved through stages of grief for this decade-long pursuit—first denying the limitations, then raging against them, bargaining for some compromise between scientific precision and human understanding, sinking into the melancholy of recognition, and finally arriving at a reluctant acceptance. It was the death of a goal that had structured my days and given meaning to my work. As with any death, the body has to be taken care of, ritualized perhaps, and laid to rest.

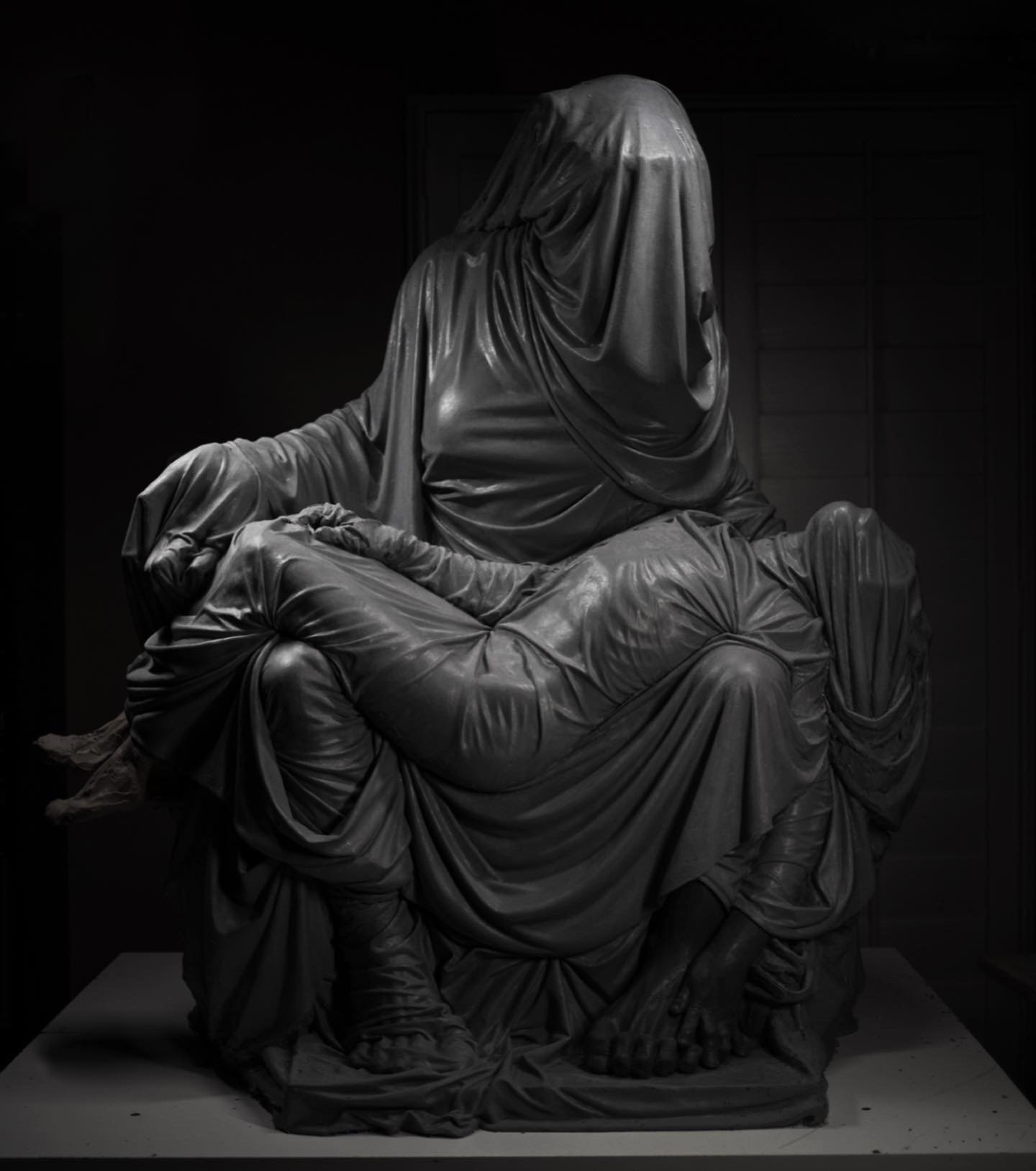

This ritual became my piece: La Piedad.

The conceptual underpinnings emerged slowly at first, then with gathering clarity. If I could not resurrect these ancient beings with scientific precision, perhaps I could honor the very mystery that surrounded them. Instead of fighting against the limitations of knowledge, I could embrace them—make them part of the work itself. I began to envision a sculpture that would embody not just what we know about our ancestors, but also what remains forever veiled.

Drawing from my own cultural background—the Christianity of my youth—I turned to one of the most iconic images of grief and tenderness in Western art: Michelangelo's Pietà. The parallel seemed fitting. Just as Mary cradles the dead Christ in the traditional iconography, I would sculpt an Australopithecus mother holding the Taung Child. This would be no anatomical reconstruction, but rather a meditation on loss that attempts to transcend time and species.

As I worked on the clay model, my mind shifted from contemplating universal loss to confronting the inevitable specific losses I would face if I lived long enough. It bears repeating: If you're lucky enough, dear reader, to stay healthy enough, live long enough, your reward will be to lose nearly everyone you currently hold dear.

I looked at the Taung Child's head, this small creature that is not quite "human" but also not too far off. This blurred manifestation of the arbitrary line humans tend to make between themselves and the rest of nature beckoned my reflection. Lucy, my small cuddly companion, laid on my lap as she usually did while I worked. I looked down at her and she looked up back at me, stretching out her neck indicating me to lower my head to gently meet hers. She enjoyed the texture of my facial hair, in this moment of nonverbal purely physical and instinctual communication.

As I sculpted this ancient child—this evidence of loss preserved across eons—my own impending loss sat purring in my lap. Her warm, pink skin with its delicate peach fuzz pressed against my hands, her visible ribs rising and falling with each breath, mirroring in their way the form of the Taung Child emerging from the clay. I felt closer to "knowing" my little hairless cat than I did my sculptural specimen I had attempted to sculpt various times. This was the first confrontation I had with the sense that I should pay clear attention to these fleeting moments I seem to take for granted. Lucy shared her life with me, and I with her since her birth when I adopted her from a stranger's house when I was in college. She had met and charmed every partner I have ever shared a room with, had traveled beyond state lines various times on my lap in various cars. So many rooms and moments I had with her, countless fleeting moments of pain and euphoria, and she remained a constant and unconditional presence in my life. In my mind there would be time to sculpt Lucy, to pay attention to her after this sculpture was carved in a few months time.

Not knowing and unable to care or understand this silent promise I had made to sculpt her, Lucy came each day or night I worked on the model to partake in my company as I finished the work. Like the fleeting sensations of her rubbing on my chin, or the rising and falling rhythm of her breath on my lap, as I worked the beginnings of the lessons this piece would teach me took shape. I looked at the sculpture and back at her, she too is impermanent. "Caretake this moment." the words came to mind as if I was commanding myself to pause and see with gratitude.

During this period, I was teaching a portrait sculpting class. On a day that was unlike the prior meetings I told my students that the day's practice session would be different. I cancelled the day's lessons and exercise and instead asked them to choose someone they deeply cared about—someone living that they loved. Today they would sculpt a relief portrait of this person. After demonstrating techniques on my chosen person, I shared how portraiture can be an act of bearing witness—a way to make someone feel truly seen. I explained how sculpture could transform attention into something tangible, something that outlasts our fleeting moments together.

After the demonstration, I could sense a slight disconnect from my students with what was now a vivid rendering of a hairless cat’s portrait on my sculpture podium in a class centered around human anatomy. I told them that I had chosen Lucy for this reflection because she had been with me for over a decade, through many chapters of my life, and I had always said I would sculpt her someday. I told them I thought I would have years to get to this piece, and that she was buried in my yard at sundown the day prior. Over the last weeks of her life she developed heart failure due to genetic complications that had been dormant for many years like a time-bomb that would upend her existence rapidly in her 11th year of life.

I could see that the weight of what I was asking them to do began to take hold. A few students held back tears but their sniffling gave their efforts away. Others smiled with glossy eyes as they understood that this lesson was also my way of processing my modest grief. "Luckily," I said, my voice steadier than I expected, "Lucy would have almost certainly not paid any mind to a sculpture of herself. But to the people that you've chosen, seeing that they've been selected as the subject for a commemorative relief centered around how much they mean to you—that might make their day, their week, or their life." I urged them not to wait to show the people they love just how much they mean to them.

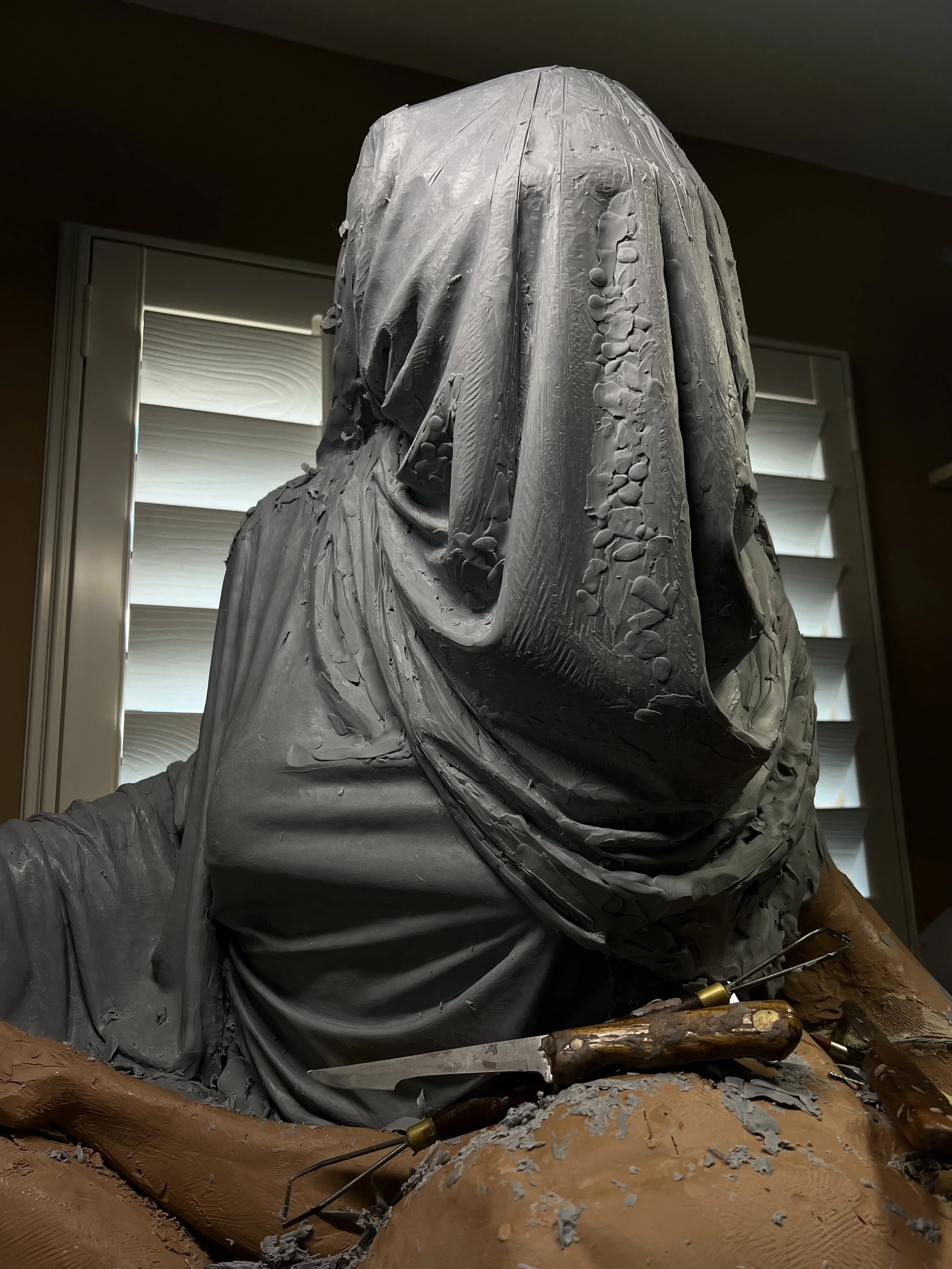

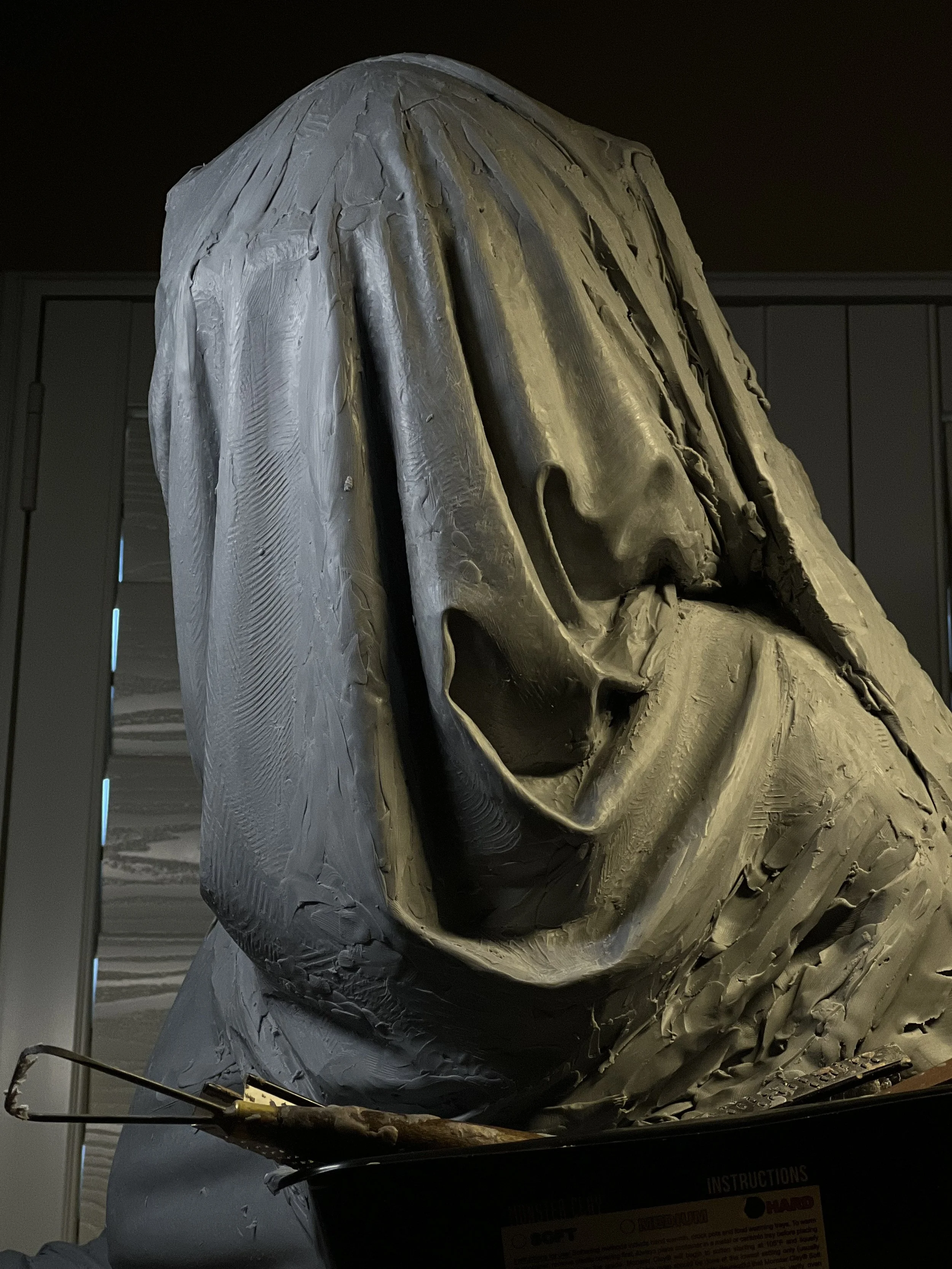

This was among one of the best lectures, demonstrations, and exercises I recall giving as a professor to date. It's clear to me now, at the time of writing this more than a year later, that it sowed a seed that would slowly take root. Lucy's death and the Taung Child's reconstruction became intertwined in my mind—two losses separated by millions of years, yet both teaching me the same lesson about attention and impermanence. For now that seed lay dormant, as in a few weeks I would be on my way to Italy to carve my meditation on loss, impermanence, and the limitations of scientific methodologies in Marble. I packed my chisels, rasps, and power tools between my modest grief and excitement for the coming adventure; to partake in a timeless sculptural tradition of breathing story and depth into stone. This time, however, unlike Michelangelo's detailed rendering focused on narrative clarity, my figures would be almost entirely veiled in intricately sculpted drapery. The cloth would flow over their forms, revealing their general shape but obscuring specific features. This veiling was not an artistic shortcut but the very point—a physical manifestation of our inherent uncertainty, our collective ignorance concerning the inner lives of others. Through the veil of sculpted cloth, La Piedad would illuminate what remains hidden without showing it.

This work that would eventually be executed in Marble, began with a life-sized clay model. As I worked, shaping the folds of drapery that both revealed and concealed the figures beneath, I began to recognize that this piece was becoming more than a meditation on our ancient ancestors. It was also, in a way I hadn't initially intended, becoming a eulogy for a version of myself—the scientific seeker who had believed that enough measurement, enough precision, enough careful reconstruction might somehow unlock the mystery of what it means to be human.

That version of me, the one who had spent countless hours with calipers and statistical models, who had published papers and presented at conferences, who had believed in the power of science to provide, if not comfort, then at least clarity—that self was being draped and veiled alongside the Taung Child. The fabric that obscured the ancient child's features also shrouded my former certainties, my former methods, my former goals.

As the drapery took shape beneath my hands, another theme emerged through the work—impermanence. The Taung Child, fossilized and preserved for 2.8 million years, represented a paradoxical kind of permanence within impermanence. The child had died, its life cut short, its consciousness extinguished. Yet through a chance fossilization, this brief existence had been preserved in stone while countless others vanished without trace.

My scientific work had been, in some ways, an attempt to push back against impermanence—to resurrect, to preserve, to make permanent again what time had obscured. But La Piedad asked different questions: What if impermanence itself is not something to resist but something to acknowledge? What if the very brevity of existence—both theirs and ours—is what gives it meaning?

The veiled mother in the sculpture held her lost child in a gesture that transcended time—a moment of grief captured in stone, yet speaking to the universal transience of all things. As I shaped her draped form, I recognized that I was sculpting not just a prehistoric loss but the essence of all human attachment—we love, knowing we will lose; we connect, knowing we will separate; we exist, knowing we will end.

And in this process, I found myself facing my own impermanence—not just my mortality, but the impermanence of my identity as an artist-scientist, as a seeker of a particular kind. That version of myself who had dedicated years to the reconstruction of ancient faces was already becoming a memory, draped and honored in the folds of this sculptural eulogy.

The decision to veil these figures in drapery wasn't arbitrary, nor was it merely aesthetic. It emerged from a series of conceptual explorations and abandoned reconstructions that preceded this work when I first began to think about the work yet ahead of me. During the summer of 2019, while taking a brief respite from my scientific endeavors, I carved an excessively veiled walking figure of the famous Australopithecus afarensis “Lucy” (who was my hairless companion’s namesake) in marble—a design based on a previously "incorrect" sculpture I had made of her skeleton. This earlier experiment had been discarded for its scientific inaccuracies, yet something about its form lingered in my imagination.

Contrary to what some might assume, using drapery isn't a simplification or shortcut in sculptural work. In fact, rendering cloth that suggests the underlying forms while maintaining its own material logic presents distinct challenges that differ from direct anatomical reconstruction. The cloth must appear to have weight and movement; it must gather, fold, and cling in ways that follow physical laws while still revealing enough of what lies beneath. This technical aspect of the work became inseparable from its conceptual aims.

The drapery became not a means of revealing but of acknowledging concealment—not an evasion of precision but an intentional recognition of limits. The task to capture the realism of the drapery offered a unique moment of reflection during the making of the work. I wasn't reconstructing the surface of the figures, rather I was physically sculpting the insecurities and limitations of the science that got me this far. The cloth flowing over the mother and child materializes the boundary between what science can resurrect and what remains forever beyond our grasp. In this way, the drapery doesn't hide the figures so much as it gives physical form to the very act of unknowing—making tangible the space between certainty and mystery that defines our relationship with the past. This echoed the mystery I felt looking at people around me and drawing them when I was younger. There was always a mystery to them that I strived to break through. This veil of ignorance was always there between my conscious experience and that of the person I happened to be confronted with. With this sculpture, it was no different, the veils don't obscure truth; they are the truth—the most honest representation of our relationship to these distant ancestors and perhaps to each other.

As such, the completed sculpture presents viewers with a paradox - figures clearly defined yet deliberately obscured. What began as my personal eulogy for a scientific pursuit transforms, in its final form, into a universal meditation on mortality and unknowing. The veiled mother and child speak simultaneously to the specificity of prehistoric loss and to the timeless experience of grief that transcends epochs. La Piedad asks viewers not to solve a mystery but to dwell within it, to recognize in these shrouded forms both what we can know and what forever eludes us.

As I completed La Piedad, I expected a sense of closure that had eluded me during years of scientific reconstruction. Instead, I found myself in an unexpected liminal space. The sculpture stood before me—a testament to transformation itself. What began as an elusive scientific quest became a hand-sculpted clay meditation, then transformed into digital information, was revived as marble through CNC technology, and finally completed through months of traditional hand carving. This dance between ancient and modern methods mirrors our own evolutionary story: we are beings shaped by millions of years of natural processes who now wield technologies that can extend our reach beyond what our ancestors could imagine. Yet for all our computational power and technological prowess, we remain creatures of flesh who must still confront the same eternal questions about mortality and meaning. Like our species—simultaneously ancient and cutting-edge—La Piedad exists in that liminal space between what we were and what we are becoming. The marble's permanence and the ephemerality of the beings it represents speak to the paradox of our existence: momentary consciousness housed in bodies crafted by billions of years of cosmic evolution, capable of both precision measurement and profound wonder. The technology merely amplifies what has always been true—we are conscious star-stuff contemplating the universe, ancestors honoring ancestors, finite beings grappling with infinity.

For weeks after completing the piece, reentering my studio lined with in-progress reconstructions, I found myself automatically pulled to improve or come up with a new aspect to focus on, as if my hands hadn't yet received the message my mind was processing. I would catch myself drafting emails to my scientific colleague about new ideas or approaches to facial reconstruction, only to abandon them half-written. The scientific language that had once been my fluent tongue now felt both familiar and foreign—like returning to a childhood home, unchanged yet somehow unfamiliar.

La Piedad had marked something significant, but it hadn't provided the clean break I'd imagined. Rather than a door firmly closed, it was more like a window slightly ajar, letting in a draft from somewhere new. The questions that had driven my scientific work remained, but they were being joined by new ones, less concerned with what humans had been and more attentive to what we are, while we still are.

The veiled figures in La Piedad seemed to be whispering something I couldn't yet fully comprehend—not about ancient history, but about the living, breathing world around me, with all its immediate mystery and wonder. The translation was still in progress, the meaning still emerging. I stood at the threshold between reconstructing what once was and witnessing what is, uncertain of my next step but sensing that my attention was being called in a new direction.